A Big Display of Glamour.

A Big Display of Glamour.

During Award Season, bedazzled by all the swirling dresses, dashing smiles and tinseled statuettes, it is easy to lose perspective on the actual point of it all: the films. At the end, the usual rabble of cynics and Debbie Downers have their share of field days, labeling Award Season an excessive and commercialized display of self-absorbed and overpaid egos rewarded in a display of luxury topping the most decadent eras of human history. The righteousness of these critics alternates with their cynicism when spouting vitriol towards participants of the big party. Yet their own sideshow is by now distorted and has created such spawn as “The Fashion Police” and The Razzies, perhaps originally critical of the excess, but now willing accomplices to the superficiality.

The Blows and Lows, Thrills and Chills of Award Season 2015: From the HFAs to the AAs

The movie makers themselves, however, are not immune and nonchalant to such venom, be it sweet or bitter, and search for depth whether it be in those message-driven acceptance speeches or in the filmmaking and nominating itself. In the throes of self-loathing and in search of some illusory “respectability”, Academy members have been shying away from bread and butter fare both in the filmmaking and in the nominating and, as a consequence, movies made are the worse for it and the nominations skew highbrow. The rise in “Independent Filmmaking” and the high correlation this year between the Independent Spirit Awards and the Academy Awards are consequences of such angst.

There used to be many more “blockbusters” that were original and good and were rewarded as such. Ben-Hur, Jaws, Titanic, Chicago, The Godfather… Commercial fare, yes, but good filmmaking too, no doubt. Award nominations (and studios) have been shying away from such films over the past ten years or so and big studio filmmaking, as Jack Black ranted in song during the Oscars, now pushes franchises and superheroes up to our eyeballs. And yet… is it all in the films?

P&A – What it Means for Results

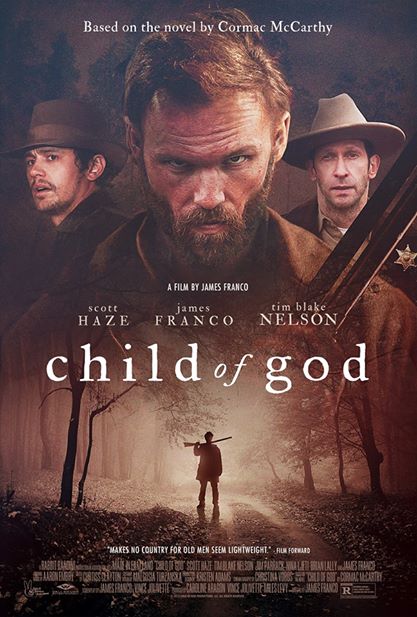

There were interesting experiments and underrated performances in 2014, such as Locke, Under the Skin, The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby, or  Child of God. Not films that would be considered to be commercial fare by any means. But two particular films are interesting case studies in what ails the movie business: Whiplash and Nightcrawler. These films deserved to be made, got made by “outsiders” and were distributed by specialties, thus qualify as “indies”. Nightcrawler came out Halloween weekend in 2,766 theaters, relying on its name to scare up some audience and with few, if any, misleading broadcast commercials. Given its mis-targeting, it fell 46% on its second weekend and whittled down to 577 theaters by its fifth week.

Child of God. Not films that would be considered to be commercial fare by any means. But two particular films are interesting case studies in what ails the movie business: Whiplash and Nightcrawler. These films deserved to be made, got made by “outsiders” and were distributed by specialties, thus qualify as “indies”. Nightcrawler came out Halloween weekend in 2,766 theaters, relying on its name to scare up some audience and with few, if any, misleading broadcast commercials. Given its mis-targeting, it fell 46% on its second weekend and whittled down to 577 theaters by its fifth week.

Whiplash had a maximum distribution of 419 theaters in its opening run and was pushed into 567 theaters after it was nominated for five Oscars a few weeks later, up from 69 the week before Oscar nominations. Not exactly wide. Even more so than Nightcrawler, Whiplash undoubtedly relied strongly on social media and word of mouth for its marketing, as very few commercials for this movie were ever broadcast widely.

Both these movies are commercial fare at the level of Silence of the Lambs, Taxi Driver, Training Day, or Tootsie. Yet no big studio took notice and Whiplash has grossed less than $12M to date. These movies were indies, and the quality of them possibly comes from such provenance, but they failed in the P&A, distribution and marketing, and did not reach the audience they deserved. They could have been contenders.

In all fairness, Whiplash, distributed by Sony Classics, opened the same week that all hell broke loose at Sony with that North Korean cyberattack thing. So they may have been otherwise distracted over at HQ.

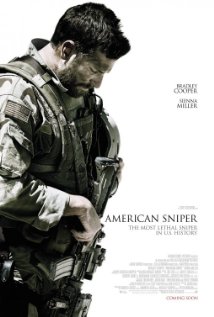

Contrast this with American Sniper. Using the classic, and yes, old school but proven, six week window for pre-opening marketing and riveting trailers during high audience Christmas movie time, its wide opening on MLK weekend was on 3,555 screens (it opened in four screens two weeks in December to qualify for the Oscars), jumping up to 3,885 screens by its fourth week of release. It fed on its own divisive controversy and cynically tied into the real life courtroom trial of the movie’s protagonist killer. Business 101.

The marketing strategy of American Sniper has been impeccable, both for its Awards Season run and for the general public, getting the film nominated for six Oscars (it took home only one, for Sound Editing) and carrying the movie all the way to third grossing film of 2014 with over $321M in ticket sales (right under Hunger Games and Guardians of the Galaxy). This for a film that goes little beyond a simplistic Cowboy & Indians portrayal of war, down to darkly clad yelling savages surrounding a flaming fort defended by heroes, and with a few token shout outs to the trauma of war for the families of the heroes and their plastic babies. Low brow fare to the max.

The marketing strategy of American Sniper has been impeccable, both for its Awards Season run and for the general public, getting the film nominated for six Oscars (it took home only one, for Sound Editing) and carrying the movie all the way to third grossing film of 2014 with over $321M in ticket sales (right under Hunger Games and Guardians of the Galaxy). This for a film that goes little beyond a simplistic Cowboy & Indians portrayal of war, down to darkly clad yelling savages surrounding a flaming fort defended by heroes, and with a few token shout outs to the trauma of war for the families of the heroes and their plastic babies. Low brow fare to the max.

Strategy Matters: it’s Show Business.

An Oscar is a superlative marketing tool for both the recipients and its associated film. Filmmakers and film executives are well aware of that and strategize accordingly from the beginning of Award Season –with the For Your Consideration campaigns– to its end, with PR and publicity campaigns in high gear.

Nominations and Wins for All Movies in Consideration

This year some of the thinking behind the scenes was transparent, and some blunders had consequences: when Paramount’s high hopes for Interstellar at the season’s start did not take off, the studio scrambled for a big winner and put its eggs into Selma’s basket, alas too late.

For whatever reason, Selma’s Oscar strategy faltered, with botched screenings of rough cuts and late mail-out screeners. The resulting dearth of nominations was then pushed by PR specialists into some sort of “snub story” to try and make Oscar history by winning Best Picture anyway. Only two other films have won Best Picture with two nominations or less: Wings, in the first ever Oscars in 1928 (nominated and winner for Best Film and Best Engineering Effects) and, four years later in 1932, Grand Hotel nominee and winner of Best Film. Tough odds in a different world.

On the other hand, after an uncertain start, Patricia Arquette sailed smoothly to Oscar gold as Actress in a Supporting Role for her characterization as the mother of that boy in Boyhood. In the water testing of the first few critic’s awards, Arquette was nominated for Leading Role, which makes sense, given that her character in fact drives the action of the movie. Some pundits even said the movie should have been called “Motherhood”.

Arquette’s performance was outstanding and award worthy and once she was slotted into “Supporting Role” her wins became a pretty sure thing, for a role with much more camera time and development than many of the others nominated in this category. We are happy that she won but it would have been less of a sure thing, and more interesting, if she had been competing against Julianne Moore and Jennifer Aniston (but that is another story) as Lead Actress.

Oscar and Guild Nominated Films and Winners

There is no question that the recipients of the Academy Awards deserved it. The Oscars are the ultimate peer review event, in which nominees are selected by people that do the same exact work (photography, editing, sound, acting, etc.) and winners are chosen by thousands of voters in the same industry, knowledgeable about how that work affects the final product: a released movie. It is indeed an honor to just be nominated, and a high recognition to win. Strategy matters and can affect outcomes, from the nominations to the wins, yet true gems can shine. Despite all the strikes against it, little Whiplash received three awards vs. one for big American Sniper. Good job. Let’s see now what this year brings.

All images and linked web content copyright their respective owners.